Music

Noh relies greatly on musical expression. Its structure, emotive tone and narrative flow are carried in great part by the singing of actors and the accompaniment of an instrumental ensemble. Music is present throughout. It begins with highly evocative tuning of the instruments (oshirabe) and continues through intoned recitations, chant and instrumental numbers. Besides some unaccompanied entrances or exits of actors, or when a stage property is brought in, music is ubiquitous.

Performers

The vocal music in the form of Noh chant (utai) plays a central role and is performed by a principal actor (shite), a supporting actor (waki), a kyōgen actor (ai) and chorus (jiutai). The instrumental ensemble and its music (hayashi) serve to accompany singing, dances, and some entrances and exits of actors. It is comprised of one pitched instrument: the nohkan (noh flute), and two unpitched percussion instruments: the ōtsuzumi (hip drum) and kotsuzumi (shoulder drum). About half of the plays in current repertoire include a third drum, the taiko (stick drum). With a few rare exceptions, taiko only joins in for the second half of a play. Between percussion strokes the drummers perform highly expressive vocal calls (kakegoe), which add an original vocal dimension to their parts.

Rhythmic Organization

The rhythmic organization in Noh is highly sophisticated, complex and carries immense dramatic potential. Its basic unit of time is an 8-beat measure (honji), which is used for all instrumental music, such as dance, entrance and exit music. Although the honji is also the basic unit of time for vocal music, it is possible to sporadically encounter measures of 2, 4, or 6 beats, used to accommodate the syllabic structure of the text. Despite this mostly fixed underlying structure, the immense flexibility of the individual beats and multiple ways of synchronization between instruments result in great rhythmic variety and expressive richness.

Flexibility of pulse is the norm in Noh. Based on expressive needs, performers intuitively adapt the beats' duration. Moreover, some beats of the eight-beat unit are extended or shrunk, predictably according to performance traditions. For instance, it is customary for the eighth beat to be extended and for beats 1, 3 and 5 to be shrunk. When the beats are shrunk the odd beat is not followed by a kakegoe. Regular pulse is almost exclusively found in dance, Noriji, and some entrance music.

The notion of strict synchronization between all players is also an exception rather than the norm. For instance, the first beat of the eight-beat unit, which for Western ensembles would traditionally serve as an accent and a point of rhythmic unity, in Noh is often silent. It is "performed" internally in the mind of the musicians a process referred to as komi. In the video showcasing strict and flexible rhythmic settings, the second, fourth and sixth beats are most of the time performed as komi as well. The sound that follows is timed according to an individual musician's sense of pacing. The notion of “togetherness” is not based on exact coincidence of the attack but on a cohesion of overall flow, energy, and expression. In the same spirit, most of the time the nohkan’s part is metrically independent from the percussion part and there are many instances when that is the case for the chant as well.

There are two types of rhythmic correlation between the voice, flute and percussion instruments. The correlation is 'congruent' when the nohkan and/or vocal parts align with the eight-beat measure (honji), whereas it is said to be 'non-congruent' when they do not. The former provides rhythmic stability, the latter rhythmic flexibility.

In the non-congruent rhythmic setting, the degree of independence vis-à-vis the eight-beat measure varies according to the instruments: A non-congruent vocal line is totally independent from the eight-beat unit, in the sense that it does not start or end on a specific beat, and at no time is it expected to align with a specific beat. A non-congruent nohkan part begins and ends at some specific points often related to the text, but the music between these two points in not synchronized within the eight-beat measure.

There is no conductor in noh. Most of the time chant or dance initiate and lead the musical flow. Jiutai and hayashi considered equal, are ancillary to the leading chant or dance. Within the hayashi, the hierarchy continues from stage right to the left. Taiko leads, if present, followed by ōtsuzumi, kotsuzumi, and finally, the nohkan. This relationships can occasionally be adjusted when one of the lower ranked instruments is being performed by someone of greater experience. At certain structural moments, it is also common that the actors wait for instrumentalist to start or finish their parts.

Pitch Organization

The melodic language of Noh is not dependent on absolute pitches. Within the hayashi, the nohkan is the only pitched instrument, yet there is no pitch coordination between nohkan and utai.

The loudness of instruments is relatively constant. The lower register of the flute is naturally softer and is used according to dramatic or formal function. The kakegoe as well as chant can match in loudness the dramatic character of the scene or role.

Form

The music in Noh draws on a common collection of rhythmic and melodic patterns. Many of the same patterns occur multiple times within a single module (shōdan), and across different shōdan of a play as well, leading to a great unity and similarity. But this seeming limitation is well balanced by the abundance of variants and tempi, a flexibility with which the patterns are sequenced into larger phrases, and by original expressive inflection of specific plays and particular performances.

For more information about patterns and the concpet of modulatiry, please refer to the page about form.

Transmission

The vocal styles, instruments with their performance techniques, as well as melodic and rhythmic language are unique to Noh, and mastering them requires many years of specialized training. Noh is taught through aural and oral transmission. Each role and instrument has its own tradition preserved and taught within hereditary schools named after their founders. There are five shite, three waki, two ai-kyōgen, five ōtsuzumi, four kotsuzumi, two taiko, and three nohkan schools. Most of them publish or hand-copy summary notation of their school’s individual parts but these are meant only as learning aids as all performances are done from memory. For more information with examples please refer to the page on Notation

About our Notation

A clarification must be made about the music notation used on this website. Conversely to Western tradition there are no complete study scores for any given play. Each of the twenty-four schools has their own individual scores and variants of notation. In the performance of a Noh play, it is the school of the shite that becomes the reference and it is the responsibility of the waki and ai-kyōgen actors and musicians to adapt their parts to the shite’s. Scores for individual instruments are written on a grid of eight blocks and they are read from top to bottom and from right to left.

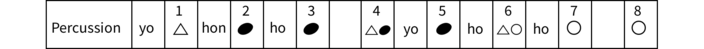

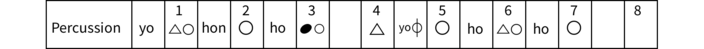

On this website, all scores combining more than one instrument are our own transcriptions. We retained the characteristic note-heads of various percussion instruments’ strokes but set them on horizontal lines. Occasionally, due to limited space we have provided summarized scores, merging the ōtsuzumi’s and kotsuzumi’s patterns into a single line.

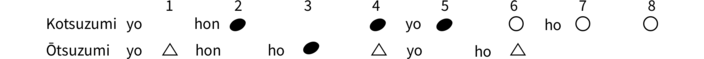

For example, the following rhythmic patterns:

have been notated as:

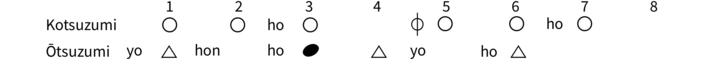

And these patterns:

have been notated as:

where the left strokes on the first, third and sixth beats corresponds to the ōtsuzumi’s stroke, the right ones to the kotsuzumi’s. We have followed the same sequencing when merging kakegoe and stroke, thus the 'yo'' on the second half of the fourth beat is called by the ōtsuzumi player at the same time as the kotsuzumi player performs a pu stroke.

Finally, when the taiko is playing with the other two hand-drums, only its part has been notated.