Vocal Sound

The vocal production in Noh is highly stylized. It is based on diaphragmatic breathing that reverberates through the head, chest and oral cavity. It should project sufficient loudness even when the singer wears a mask.

The vocal tone-center is relative. The first person who starts a chant instigates the central tone, and that tone range is informed by the character he is impersonating. The secondary actor signals his lower position by providing lighter, faster and higher tones (for example, Wakizure in Kokaji). Larger width of the range indicates the protagonist is a man while a narrower range indicates a woman.

There are two general styles of utai: spoken and chanted. Both are intoned in full voice, but never in falsetto.

Spoken

The spoken sections, called kotoba, consist of unmetered prose. Usually the recitation divides a sentence into two parts: a gradual rising tone reaching a peak followed by a falling off. The highest tone falls on the second syllable of the second part. In the text transcription of the excerpts, syllables in bold identify the higher tones that lead to a descent.

Sections in kotoba are always delivered by an actor or two, but never by the jiutai. When considering the dramatic unfolding of a play, the difference between the two is important. The text delivered in kotoba by a single actor tends to be factual, whereas spoken text between two actors usually carries information that furthers and nourishes the unfolding drama.

The difference in style between the shite's and waki's kotoba can be heard in the following three examples:

Kokaji – Mondō

The Mondō from Kokaji is a spoken dialogue between the shite (a divine being) and waki (sword maker). The former sits on the left, and the latter on the right. This example offers two points of comparison between the kotoba styles of shite and waki.

The first point relates to the gradual rising tone. While they both use a rising line to get to a peak-tone, the overall ascent of the shite’s line is more subdued compared with the waki’s. The second point relates to the rhythm of delivery, since the shite’s is much slower than the waki.

Chanted

The chanted music, called utai, can be sung in two different styles: yowagin, a gentler melodic singing, and tsuyogin, a more forceful and dramatic style.

Yowagin

When singing in yowagin style, the actor uses a modest vibrato, producing melodies with perceptible stable tones. This style is common in passages expressing elegance and pathos.

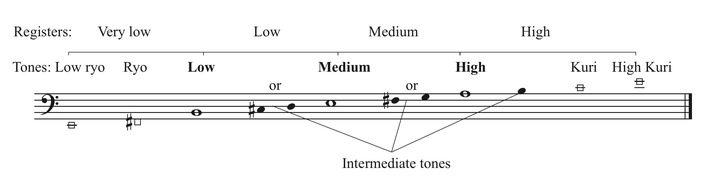

Even if the tonal center of a chant in Noh is not absolute and is instead determined by the performer, the chant’s intervals are fixed. The entire range covers two octaves and is divided into four register zones: Very Low, Low, Medium, and High, each one covering more or less the span of a perfect fourth.

Since tones are relative, they are referred to by a general name. The three most important tones are the Low, Medium, and High (in our example B2, E3, and A3 respectively), and the majority of the chants are set around these three nuclear-tones. Intermediate tones are used to melodically flow from one nuclear-tone to another.

Finally, the lower and higher ranges are extended with the addition of the low ryo and the ryo (E2 and F#2 respectively) for the former, and the kuri and high kuri (C4 and E4 respectively) for that latter.

Hagoromo/Kuri

The module is named after the kuri tone from the higher register. For the most part, the melodic material of the piece focuses on the High tone with few incursions on the kuri, shown in bold in the text of the video.

Upon reaching the kuri’s signature cadential melisma, the hon-yuri, the melodic material switches to Medium before cadencing on the Low. (The pitch material in this performance is a major second lower than the one shown in the figure above).

The registers in the video are symbolized by the following letters: L (Low), M (Medium), H (High), K (Kuri).

Tsuyogin

While singing in tsuyogin style, the actor uses a notable vibrato with utterances usually contained within a small range span. This style is used for most dramatic passages expressing events and emotions like celebration, excitement, bravery, or solemnity.

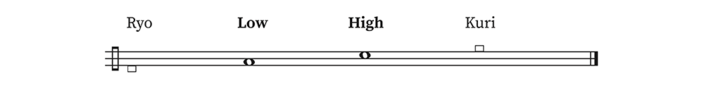

The actors do not attempt to produce specific melodic tones. Their singing oscillates mainly within a minor third shown below as Low and High tones. However, at specific moments the High tone is embellished with higher ones.

Kokaji/Kuri

The section's name refers to the high tone kuri, so this section's melody is set in the higher register.

The registers in the video are symbolized by the following letters: L (Low), H (High), K (Kuri).

Vocal Rhythm

The vocal parts fall into two main categories of rhythm: congruent when their parts align with specific beats, and non-congruent when they do not.

Congruent (hyōshi-ai)

A Noh chant is said to be congruent when its syllables coincide with the measure’s beats. There are three possible congruent settings: hiranori, ōnori, and chūnori.

Hiranori

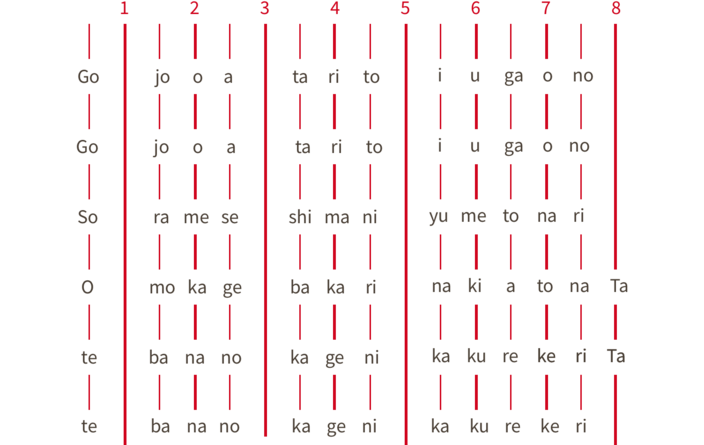

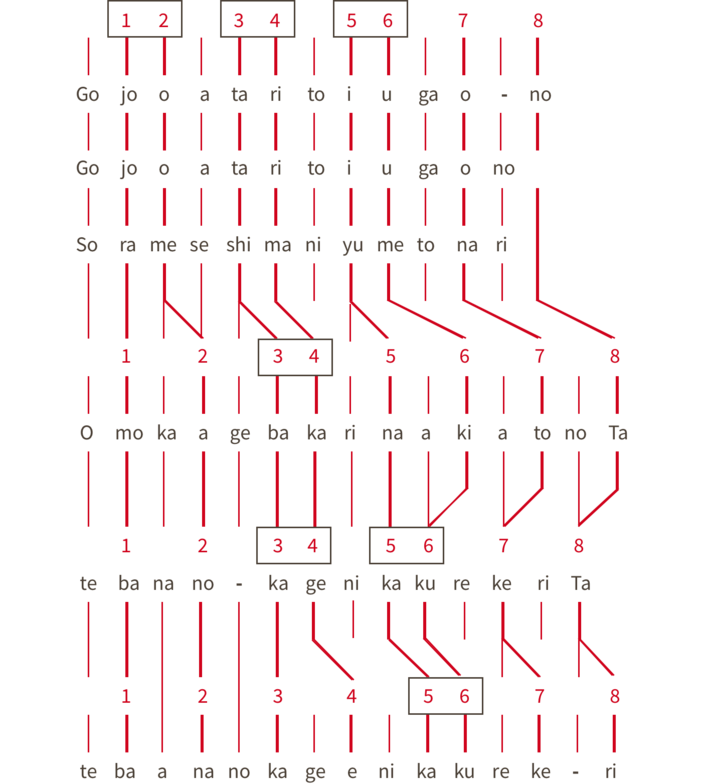

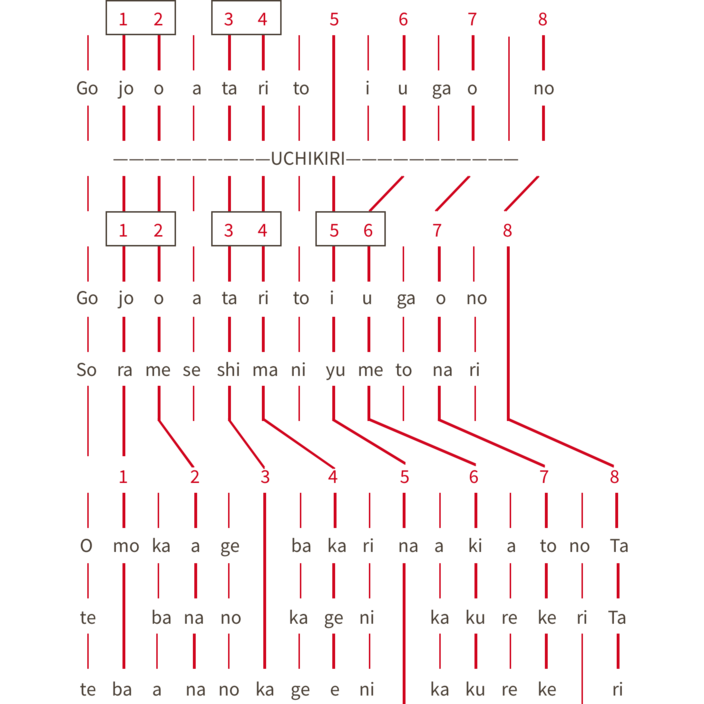

Verse consisting of alternating lines of seven and five syllables is the most lyrical and elegant form of Japanese poetry, as seen in haiku, waka, and renga, among other poetic forms. Hiranori is the basic rhythmic form used in Noh where the poetic twelve syllables match with the honji’s eight-beat. Considering that there is a possibility of two syllables per beat for a total of sixteen syllables per honji, this leaves space for four caesuras. The standard positions for the caesuras are on beats 1, 3, 5 and 8, dividing the honji in two asymmetric hemistichs: one of four beats and a half, the other one with three beats and a half.

The hiranori setting has two singing styles: tsuzuke-utai and mitsuji-utai. The explanation of the two individual styles is followed by a demonstration in context, which shows how they can complement each other in a chant. The following examples are based on Hashitomi’s first Ageuta.

In tsuzuke-utai, singers hold syllables over the first, third, and fifth beats, so that the twelve syllables fit within the honji. In other words, the text is manipulated for the benefit of a steady metric structure, and the eight beats of the unit are divided periodically.

The example below shows an academic distribution of the twelve syllables in two groups of seven and five; the group of seven syllables broken into 1 + 3 + 3, with the first syllable starting on the upbeat preceding the very first beat. The figure also shows that the syllables preceding the first, third, and fifth beats are held over the downbeat, as if to avoid competing with the drums' strong strokes that usually fall on at least one of these downbeats. The fourth caesura occurs on the eighth downbeat in order to separate the two lines.

Here is a more dynamic distribution of the four caesuras, with a setting that follows the grammatical structure of the text.

Hashitomi/Ageuta-1

When singing in mitsuji-utai, syllables rarely carry over since the honji is condensed to fit the text. In other words, the metric structure is manipulated for the benefit of the text's declamation. Therefore, the eight beats of the unit are not periodic. Compared with tsuzuke-utai, a setting in mitsuji-utai is more dynamic since the melodic momentum is rarely interrupted by held-over tones.

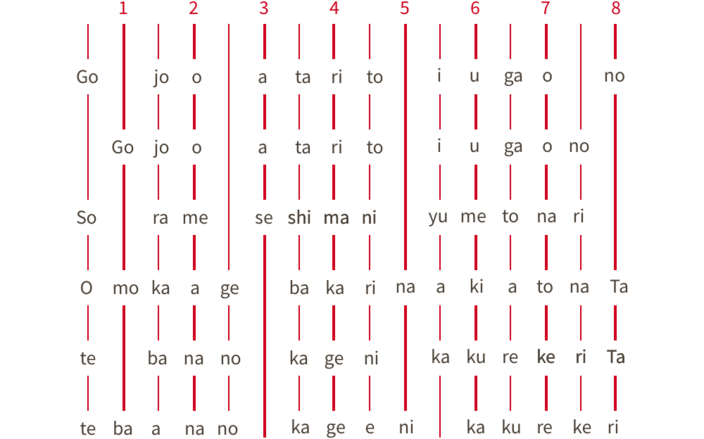

Here is the text from Hashitomi’s first Ageuta set in mitsuji-utai, where the condensed first, third, and fifth beats appear in boxes.

Hashitomi/Ageuta 1

In the context of a chant, performers use mitsuji-utai and tsuzuke-utai alternately to vary and control the rhythmic flow of the chant. The changes from mitsuji-utai to tsuzuke-utai are not left at the discretion of the performers though; rather the music is prescribed, and it typically includes back and forth transition between the two. The cycle mitsuji- to tsuzuke-utai always starts with mitsuji-utai leading to tsuzuke-utai, which either creates a cadential pattern or to another mitsuji-utai, to start another cycle.

It is noteworthy that performers usually use sparse mitsuji percussion patterns to accompany the part of a chant set in the declamatory mitsuji-utai, where the limited number of percussion strokes is counter-balanced by the melodic line unfolding with few or no rests. On the other hand, the regular tsuzuke patterns usually accompany part of a chant set in the tsuzuke-utai, where syllables held over to accommodate the measure’s eight beats create rest in the melodic line counter-balanced by the steady percussion strokes.

Here is the actual text setting for the first Ageuta from Hashitomi. Because this chant is rather short, it includes only one motion from mitsuji-utai to tsuzuke-utai, with the first three lines set in mitsuji-utai, accompanied with sparse mitsuji patterns in the percussion, and the last three in tsuzuke-utai accompanied with steady tsuzuke patterns in the percussion.

As is typical of an Ageuta, its first sentence is repeated. The iteration is preceded by an uchikiri.

Hashitomi/Ageuta 1

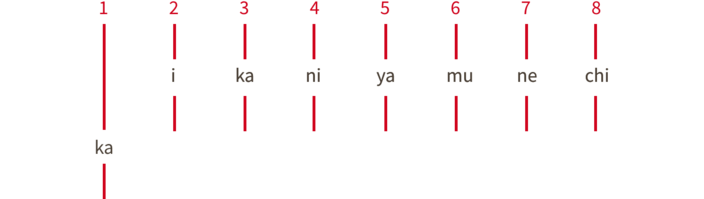

Ōnori

A text setting in ōnori has one syllable per beat. The first syllable of each line of text comes on the second or second beat-and-half. Because of its periodic quality, this text setting is often used before or after a dance or in the concluding module (shōdan) of a play, the Kiri.

Kokaji/Noriji 2

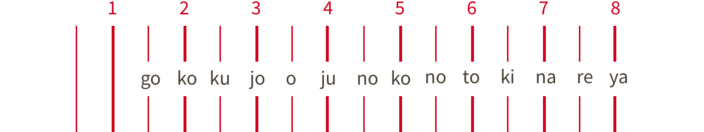

Chūnori

Text set in chūnori has two syllables per beat. The first syllable of each line of text typically comes on the first or first beat and a half, with a complete line finishing within the span of a single honji.

Because of its lively quality, this text setting is often used for description of an active moment, such as a battle. Although, it is common practice for a shōdan whose text is set to chūnori to also include passages set in hiranori, the eight-beat units (honji) is almost never contracted, like in mitsuji-utai, rather it remains steady.

Kokaji/Kiri

Text setting exceptions

Occasionally, lines of text do not fit within the 7 + 5 model. The number of syllables for the first hemistich can vary between two and ten, and three and eight for the second one. There are two methods that allow for the rhythmic adjustment of syllables: the first one involves starting the line's first syllable on a different beat, whereas the second method involves the insertion of measures of various sizes.

The standard position for the first syllable of a line of text is on the upbeat leading to the honji's first downbeat. Thus, one method of fitting a larger than twelve syllables line of text within a honji consist of starting its first syllable earlier than the standard upbeat to the first beat. For example, the last line of text of Hashitomi’s first Ageuta is comprised of thirteen syllables: 8 + 5.

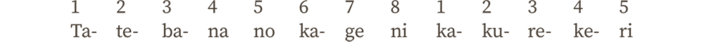

In this case, ‘Ta,’ the first syllable, starts on the eighth downbeat as seen below instead of the usual upbeat to the very first beat:

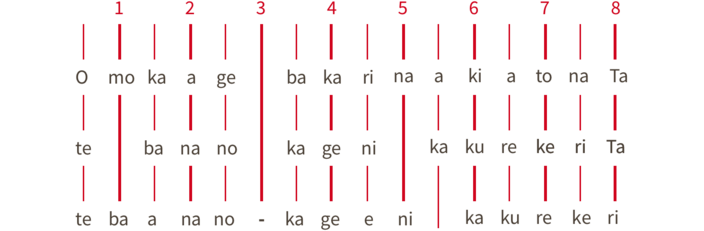

The second method of setting lines of text that exceed twelve syllables consists of introducing measures of two (okuriji), four (toriji), or six (kataji) beats. For example, here are the first three lines of Kokaji’s Kiri. Its syllabic structure is: 7 + 5, 7 + 6, and 9 + 5.

A toriji (measure of four beats) has been inserted between the second and third honji (eight beat unit) in order to counter-balance the odd syllabic structure of the text. When it comes to measures other than the honji, the toriji is far more common that the two- and six-beat measures.

Non-congruent (hyōshi-awazu)

The emphasis for non-congruent chants is on the text and melodic line. With this text setting there is no coordination between syllables and the unit’s eight beats. There are two types of non-congruent chant: sashinori and einori.

Sashinori chant is always accompanied by the ōtsuzumi and kotsuzumi in a flexible setting, while einori chant can be accompanied by the hand percussion instruments in either strict or flexible setting. If the chant includes a nohkan part it will also be non-congruent.

Sashinori

Sashinori chants are sung in a recitative style, accompanied by the ōtsuzumi and kotsuzumi in flexible setting, favoring the sparse mitsuji patterns. On the other hand, the Kuri also accompanied by the two hand-drums in flexible setting, favors the tsuzuke pattern. There is a Japanese expression that describes well the idea behind a non-congruent chant accompanied by percussions in flexible rhythmic setting: fusoku furi which means ‘not separate but not together’.

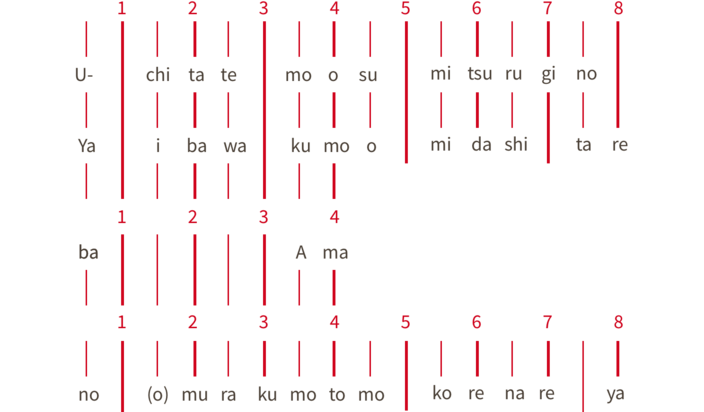

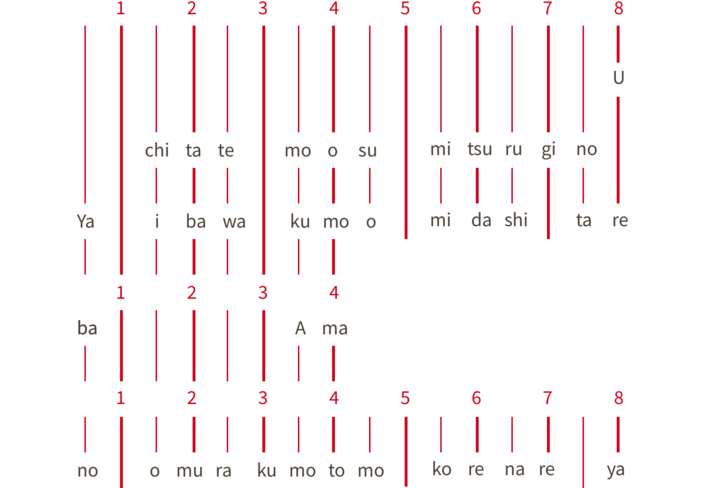

The Sashi from Kokaji, sung in tsuyogin mode, is composed of two parts. Each one begins by a solo performed the shite followed by a reply by the jiutai. The reply is broken up into melodic lines rhythmically characterized by a slightly accelerated pulse that becomes a sustained tone. The sustained tones are positioned on syllables that reinforce the text's structure or meaning. For the most part, each line stays on the high tone, usually preceded with an inflection from below. Finally, the chant concludes on the low tone.

The score provided for this excerpt shows the first part is composed of six lines, each concluded by a sustained tone: the shite presents the first, the jiutai the next five, identified in the score with the numbers 1 to 6. It is the two percussionists' responsibility to position their four mitsuji patterns against these six lines.

Kokaji/Sashi

Einori

Einori chants are usually accompanied by the ōtsuzumi and kotsuzumi in strict setting. The Issei-chant from Hashitomi is sung in yowagin style, focusing on only four tones: the Medium and High, and their respective Intermediate tones a second lower. It is divided up into two segments: the first one sung by the shite, the second one by the jiutai.

The hand-percussion instruments start both parts with sparse mitsuji patterns before moving on with tsuzuke patterns. It is while performing the mitsuji patterns that the ōtsuzumi player has some flexibility to adapt to the melodic line. This is particularly clear with this recording. The ōtsuzumi player uses flexible kakegoe when performing the first mitsuji patterns, whereas the kotsuzumi player uses the strict kakegoe throughout the chant.