Nohkan (Flute)

There are three nohkan schools: Morita, Issō and Fujita. Featured MORITA Yasuyoshi, and all musical examples are from the Morita tradition.

Sound

The scale of this seven-hole instrument, member of the traverse flute family, is unusual because of a thin bamboo tube called nodo, inserted between its mouth hole and first finger hole. The nodo distorts the natural acoustic behavior of the pipe and as a result, its scale consists of microtonal pitches that do not fit any predefined mode and vary from instrument to instrument. According to some sources, the nodo helps produce hishigi, the highest pitch on the instrument, and is a crucial note of structurally important patterns.

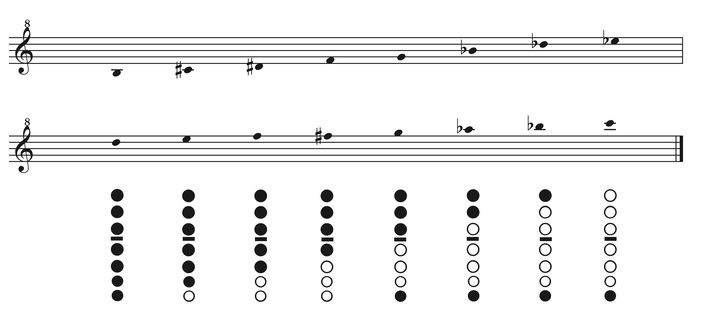

The following figure shows the approximate principle pitches produced by one particular nohkan (half-hole pitches were not recorded). The row of pitches on the second system are the continuation of the first and are produced with an increased airflow using the exact same fingerings as the first. In the case of most world flutes, as well as other Japanese traverse flutes like the ryūteki, komabue, and kagurabue, such overblowing would consistently produce pitches an octave higher and as a result, extend the same scale. In the case of nohkan, the overblowing of the lowest note creates a pitch that is a minor tenth higher, and with every following note, that interval diminishes so the resulting interval of overblowing the highest note is a major sixth. The increased air pressure process adds a new set of pitches to the overall scale.

Whereas Western flutists use the distal phalanges to cover the instrument's key and holes, the nohkan players use their intermediate phalanges allowing for very subtle half-holing that produces additional microtonal fluctuations in the pitch.

The microtonal and unregulated pitch material of the nohkan functions independently from the singers. The primary actor during a performance sets the chant's central pitch, independent from the nohkan's pitches. The overall compatibility of energy and pitch responds to the circumstances and spirit of a particular performance. This freedom between the pitch material of the actors and the nohkan is also facilitated by their separation in range, since the nohkan much higher than the chant.

The mode of attack is another important factor that adds to the richness of nohkan's sound palette. When enunciating a new note, the air pressure controlled by the diaphragm allows for different sharpness of attacks from sudden to slurred. Tonguing, a common performance practice of the West, involving making a silent use of syllables like "ta" or "da" to break the flow of air, is not used.

Melodic Patterns

The nohkan creates an ambiance that reflects the particular emotions of the play, the status or psychological mindset of a character in a given shōdan, and underlines the dramatic structure. This is achieved using a collection of just over a hundred melodic patterns and pieces that are shared between different plays. This fixed melodic repertoire consists of different kinds of material: ashirai patterns, which are relatively short and are used multiple times throughout each play; special patterns associated with particular emotions or situations, such as love, shinto rituals, purifications, or mantra chanting; pieces that accompany dance, entrances and exits; and pieces used exclusively for kyōgen. In Morita school, there are around 20 ashirai patterns, 80 special patterns and pieces for entrance, exit and dance (the number includes variations such as different introduction patterns for dances) and 12 pieces for kyōgen. Performers inflect expressive characteristics on the same patterns, which serve the demands of a specific play, section and structural moment and add to the immense richness of the nohkan music.

To help the user better appreciate the expressive transformation of the same pattern, we asked MORITA Yasuyoshi to perform 'generic' versions of some patterns, whose use in the two plays can then be compared. He was at first reluctant, since no 'generic' versions are ever performed. Patterns are always learned and played in the context of a specific play, with a particular character in mind. We appreciate the exception he made for this website and its educational purpose. Within the catalogue that follows, three patterns, naka no takane, takane mi kusari, and tome no te, are first played in their 'generic' form and then played as performed in Kokaji Kuse, involving a male god, as opposed to Hashitomi Kuse, which involves a young maiden.

The transmission of music for nohkan is primarily oral. To help memorization, performers use a system of mnemonics, called shōga. These are also notated. Specific combinations of syllables represent specific melodic contour. The use of vowels suggests the direction of pitch; if ordered from highest to lowest, these are i, a, o and u. However, there is no fixed relationship between a single mnemonic syllable and specific pitch or fingering. As a result, written notation has only a secondary role and is not sufficient. Examples of mnemonics include o, u, hi, ra, ri, ru, ro, hya, hyu, and hyo, among others. For example, the shōga for takane is "o-hya ra." It is important to note that each syllable represents a sound often composed of a sequence of pitches rather than a single one. Shōga does not carry any information about its duration, since it changes depending on context.

Finally, a word about the hishigi, a shrill, high-pitched tone that is rarely used within melodies. It is used primarily as a powerful and striking effect sometimes described as an invocation of the gods. It often marks the end of a play, or the beginning or end of a shōdan.

Selected Examples

In presenting this selection of melodic materials, our objective was to record only the principal nine ashirai patterns that can be heard in one or both of the plays featured on this website: Kokaji and Hashitomi. For some context, in the notation book of Morita School, fourteen patterns appear in the play Funabenkei, only five in Soshi Arai Komachi, fifteen in Kokaji, and eight in Hashitomi.

- Takane

- Takane hane

- Hishigi

-

Hishigi takane

mi kusari - Roku no ge

- Miroku no ge

- Naka no takane

- Takane mi kusari

- Tome no te

To illustrate how patterns articulate the structure of a shōdan, we will use the example of an Ageuta. Three melodic patterns are usually performed during an ageuta: takane, naka no takane, and mi roku no ge. They stand out because they are relatively short, and each appear only once and as distinct utterances, played at their own specific point in the shōdan.

First, the sequenced patterns accentuates the melodic shape of the chant, which starts in the higher range, moves to the middle, and closes in the low range. This descent is imitated by the nohkan's sequence of patterns, which start with takane followed by naka no takane, both in the instrument's higher range followed by the mi roku no ge, whose melodic contour moves from the instrument's medium range to the low.

Second, the positioning of the patterns also underlines the structure of the text, which is characterized by a repeated first and last line. The reiteration of the first line is preceded by the nohkan's takane pattern, while the first statement of the last line of text is underlined by the entrance of the mi roku no ge pattern. The naka no takane does not have a specific position, but it is usually played when the vocal line is about to move from the higher to the medium range.

There are exceptions to this basic structure. For instance, the naka no takane is left out from the first Ageuta from Hashitomi, shown in the video. Its second Ageuta is even shorter, and only includes the first nohkan pattern, takane.

Rhythm

The nohkan performs solo, with the percussion instruments or with percussion instruments and voice. It never plays with the voice alone. For the majority of its repertoire, the nohkan’s part is non-congruent, meaning that it is not synchronized to specific beats within the eight-beat unit. Depending on the situation, the nohkan player relies on either the text, the position of an actor on the stage, or an approximate point within the eight-beat unit to determine the beginning and end of a melodic pattern. For instance, when playing the solo piece Nanoribue, an entrance music commonly played as the waki is walking onto the stage, the pace of the performance is guided by the time taken by the actor to walk from his entrance point to the speech position.

The Nanoribue presented in the next video, is based on three ashirai patterns: naka no takane, roku no ge, and an unnamed third one exclusive to the Nanoribue.

When performing with the percussion instruments, there are three different types of possible rhythmic arrangements:

1. The nohkan part is congruent

2. The nohkan part is non-congruent and set against a strict

percussion part.

3. The nohkan part is non-congruent and set against a flexible

percussion part.

Congruent

The nohkan part is 'congruent' (awase-buki) when it aligns with specific beats of the honji. This is most typically encountered in dances and entrance and exit music. In these instances, the nohkan’s melodic patterns almost always start on the honji’s second beat or its second half. Its material is developed from short motives that are juxtaposed to create a larger melodic cell. For instance, the melody that accompanies the dance Maibataraki, found on this website, is composed of three melodic motives —a, b, c—, where each letter corresponds to an eight-beat melody. These motives performed as a set create a twenty-four-beat long melody. On the other hand, the Jonomai’s core melody, called Ji, is composed of four patterns, each eight-beats long, labelled Chū, Kan, Kannochū, and Ryō.

Non-congruent in Strict Setting

A nohkan's part is 'non-congruent' (ashirai-buki) when it does not align with the beats of the honji. We’ve included an example of it against a strict percussion part in an excerpt from the Issei-music from Hagoromo. This is an entrance music that typically leads to the Issei-chant, in which the percussion’s strict rhythmic setting is maintained against a non-congruent chant. After having articulated the beginning of the module with the Hishigi pattern, the nohkan players waits for the fourth honji to freely position the naka no takane pattern in the span of two honji.

Non-congruent in Flexible Setting

We provide an example of a non-congruent nohkan’s part against a flexible percussion part in an excerpt from the Shidai-music from Atsumori. This is an entrance music that typically leads to the Shidai-chant, in which the percussion setting switches to strict against a congruent chant. After having articulated the beginning of the module with the Hishigi pattern, the nohkan players waits for the fourth honji to freely position the Takane mi kusari pattern in the span of two honji. .