Masks

By Diego Pellecchia

Introduction

There are over 200 types of noh masks, grouped in categories, types, and variant types. One of the most common subdivisions conceives of five groups: god masks, female masks, male masks, spirit masks, and demon masks. Masks used in the ritual performance Okina constitute an additional category. Kyōgen masks are categorized separately.

Most noh masks are associated with a character type (e.g. young woman, middle-aged woman, warrior, demon, etc.) and each shite school may prescribe a certain character in a specific play to be performed with different types of mask. There are only a few masks that are used exclusively to portray one character (e.g. Yamamba, Shunkan, Semimaru). Also, while most mask types are employed across schools, some others are specific to certain schools. For example, the same role of young woman may be portrayed with a woman mask called Waka-onna (Kanze school), Fushiki-zō (Hōshō school), Magojirō or Ko-omote (Kongō school), or Ko-omote (Konparu and Kita schools).

Masks developed throughout the Muromachi period (1338-1573), and their use was canonized at the beginning of the 17th century. In the late 16th century, certain masks from each type were seen as superior and became standards (honmen) that were then copied using techniques that are still used today. Each of these honmen has a name (e.g. Kojō, Chūjō, Tobide), which is retained as the name of the copy (utsushi), thus establishing identifiable iconography for each name-type. Excellent utsushi masks made according to the dimensions and expression of the honmen became viable theatrical tools and are seen as having their own intrinsic identity. As honmen are used as reference masks, the process of creating utsushi naturally results in the creation of a great number of spin-off masks, expanding the range of choice in the portrayal of a character.

Noh masks are carved using only natural materials and hand tools. A single block of hinoki (Japanese cypress) is carved into the shape of the mask, then it is covered with a white primer made with crushed shell and animal glue. The mask is then painted with natural pigments and, depending on the type, is covered with thin layers of brownish paint which create a patina of age while giving depth and highlighting details. Finally, the carver may deliberately scratch or scar parts of the mask to give it an ‘older’ look. No fixing agent or varnish is added on top of the mask, making it prone to further damage.

Today both ancient masks and copies are used in performance. Regardless of age, actors treat masks with the utmost care, bowing to them before using them in performance to express respect for the tradition they represent. It is thanks to this carefulness that ancient masks can still be used on stage today, after centuries of use.

Hashitomi

Mask: ‘Ko-omote’

The name of this type of mask means ‘small face’. The use varies depending on the shite school. Kongō school uses Ko-omote to portray any kind of young female character: from a country girl to a court lady, from a flower spirit to a goddess.

Ko-omote represents the idealized face of an aristocratic young woman from the Heian period (794-1185), which was considered as the standard of elegance in medieval Japan. Ko-omote masks feature a fair complexion, with three thick hairlines neatly combed along the sides and fuzzy eyebrows painted high on the forehead. The teeth are dyed black. This make-up and hairstyle follow Heian-period aesthetics, though the mask may be used to portray any kind of female character, even from later eras. The mask’s plump cheeks and small lips, and the proportions of the small triangle formed between the eyes, nose and mouth give the mask a youthful look.

The mask is used in combination with a, long black wig (kazura) which, in the case of Hashitomi, is kept bound behind the neck, and hidden under the upper garment. The hair wig is parted in the middle and combed along the sides of the face, in correspondence with the painted hair. The ears of the actor are hidden under the hair.

In the case of Hashitomi, Ko-omote is the standard choice in the Kongō school to represent the face of Yūgao, a young aristocratic lady from the Heian period. The Kanze school uses Waka-onna, offering the alternatives of Ko-omote and Fukai, the mask of a middle-aged woman. The Hōshō school uses its standard young woman mask, Fushikizō.

Shimo-gakari shite schools (Konparu, Kongō, and Kita) schools use Ko-omote for both shite and tsure (companion) roles, though they often distinguish between specific Ko-omote masks reserving certain ones for shite roles and assigning others with less complex expressions for tsure roles. The Kongō school treasures one of the most famous Ko-omote masks, called Yuki-no-Ko-omote (snow Ko-omote), which is said to have been created by the renown mask carver Tatsuemon in the Muromachi period (1338-1573).

Kokaji

First Act Mask: ‘Dōji’

The name of this mask means ‘boy’. The mask is used invariably for either a deity or a spirit in disguise in the first half of a play (e.g. Tamura, Kokaji, Shakkyō) or for roles of Chinese immortal (Makura-jidō, Hōsō, etc.). According to nō conventions, masks are not used for roles of adult males, unless the character is the personification of a supernatural creature or some other kind of special character.

The mask represents the face of a boy, with natural eyebrows, elongated eyes, and a natural smile. The expression is devoid of any wrinkle or furrows, contributing to a youthful look. The painted uncombed hair suggests a young age and is matched with the large black kashira wig used in combination with this mask.

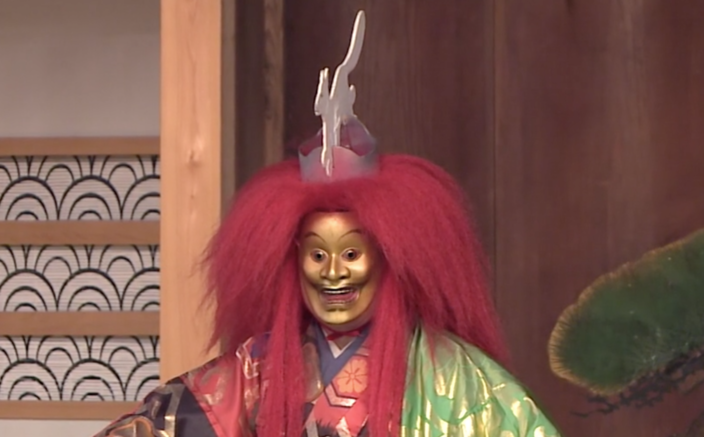

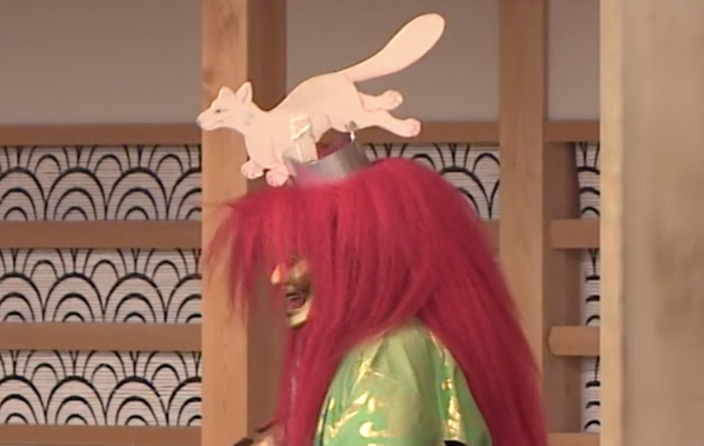

Second Act Mask: ‘Kotobide’

The mask used in the second half of the play may depend on the shite school and on the performance variant. The typical choice for the standard version of the play is Kotobide. The name of this mask means ‘small jump/pop-out’ and it describes its eyes, which appear as if they were popping out of the eye-sockets. ‘Small’ refers to the fact that there is a ‘large’ version of the mask (Ōtobide), used in other contexts. Kotobide is used for roles such as the deity of Mt. Inari in the form of a fox-god ‘(Kokaji) or the evil fox-spirit Tamamo no mae (Sesshōseki).

While the standard Kotobide has a reddish complexion, in the Kongō school performance analyzed in this website a variant type of the same mask, called Dei-kotobide (‘golden kotobide’) was used instead. Dei-kotobide is entirely covered with gold paint and features golden metal inserts for the eyes. According to noh conventions, gold symbolizes the supernatural nature of a character. The arched eyebrows, open wide round eyes, open mouth, and pointed mustache give the impression of an outburst of energy. Depending on the school and performance variant, the mask is used in combination with red or white kashira wig.

The sculptural features of a mask differ from item to item. The one used in the performance filmed for this project is essentially the same as the standard Kotobide, except that its surface is painted gold instead of red. However, other Dei-kotobide are closer to the larger Ōtobide, which is used for the rain and thunder deity Wake-ikazuchi in Kamo, or for performance variants of Kokaji.

The mask used in the performance filmed is a Dei-kotobide carved by Iseki Bitchū no jō (Momoyama period)

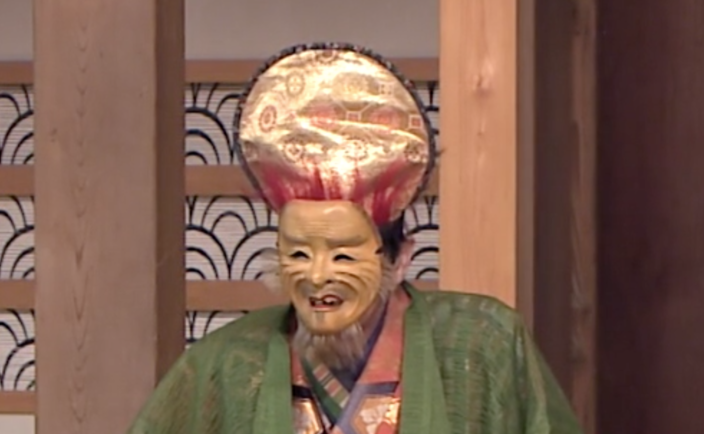

Ai-kyōgen Mask: ‘Noborihige’

Kyōgen masks tend to have exaggerated features and are often used to portray supernatural characters. Noborihige mask represents the face of a smiling rustic old man. Its name means ‘raising beard’, referring to its bristling-up sideburns. Other features are deep wrinkles, a toothless smile, and eyes carved in the shape of circumflex accents. Noborihige is mostly used in ai-kyōgen interludes for roles of massha (subsidiary deity) but may also be used for other kyōgen roles.