Notation

Although chant, dance, and music are transmitted aurally and orally from teacher to student, notation has had an important role in supporting the accuracy and ensuring the authenticity of the transmission throughout Noh’s history.

Chant – utaibon

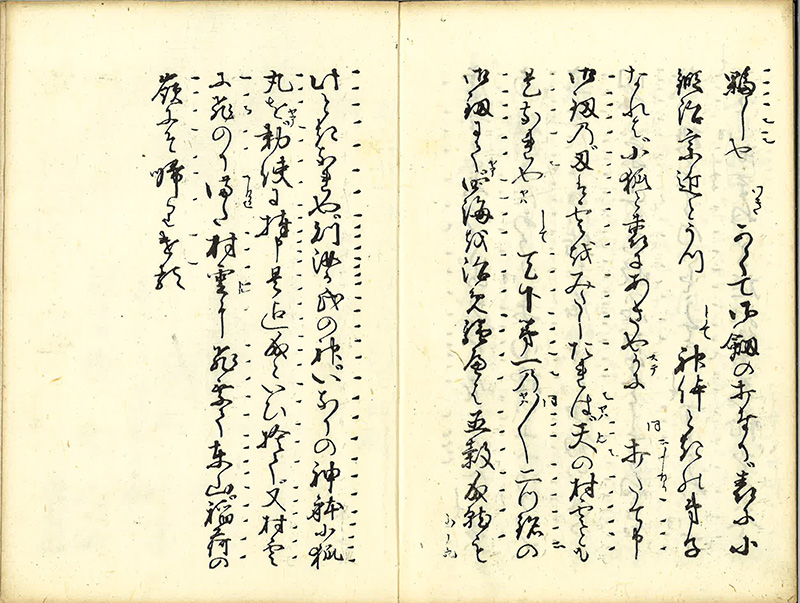

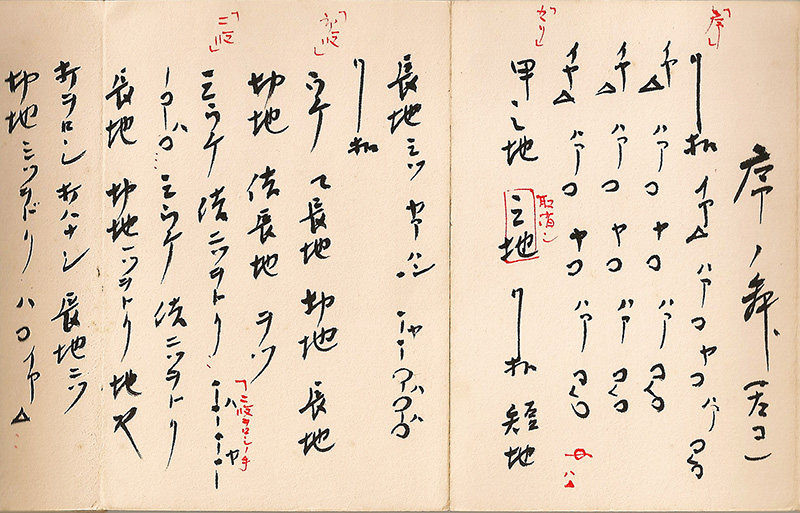

The most popular and important notation for Noh drama is the utaibon, which means ‘chanting book.’ Compared to a libretto, a utaibon contains the dramatic text of a Noh play with the indication of roles including the shite, waki, and jiutai. However, it does not include Interlude section between two acts, performed mainly by ai-kyogen, because the utaibon functions more like a chanting notation rather than a play script. Sung text is annotated on the right side of the notation with dot-like signs indicating how each syllable or line is sung (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Kokaji. Edited by Kongō Ukyō. Published by Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo in 1898.

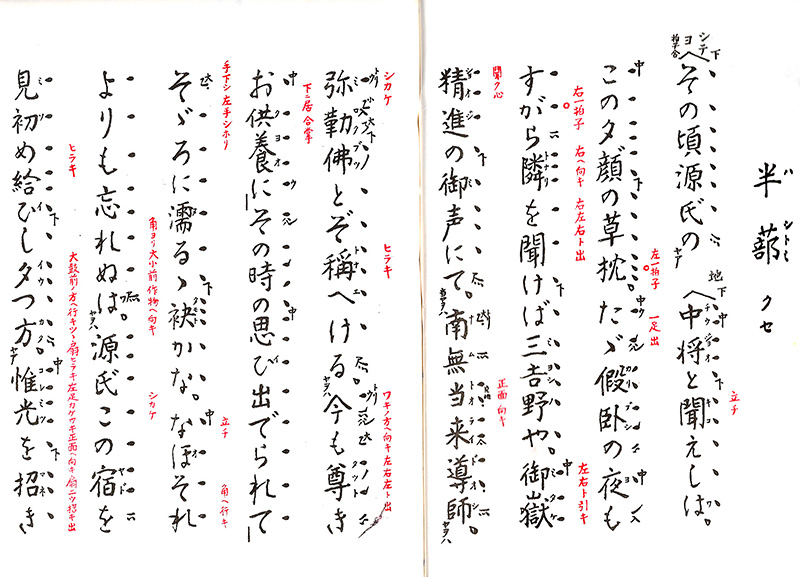

After 17th century, as the amateur population was growing, the utaibon was printed repeatedly, becoming one of bestsellers through the Japanese history. 20th century’s utaibon has been revised to include the synopsis, costumes, and masks used on stage rather than as a mere notation for chanting (Fig.2).

Fig.2 Kongō ryū yōkyoku bon: Kokaji. Published by Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo, published year unknown.

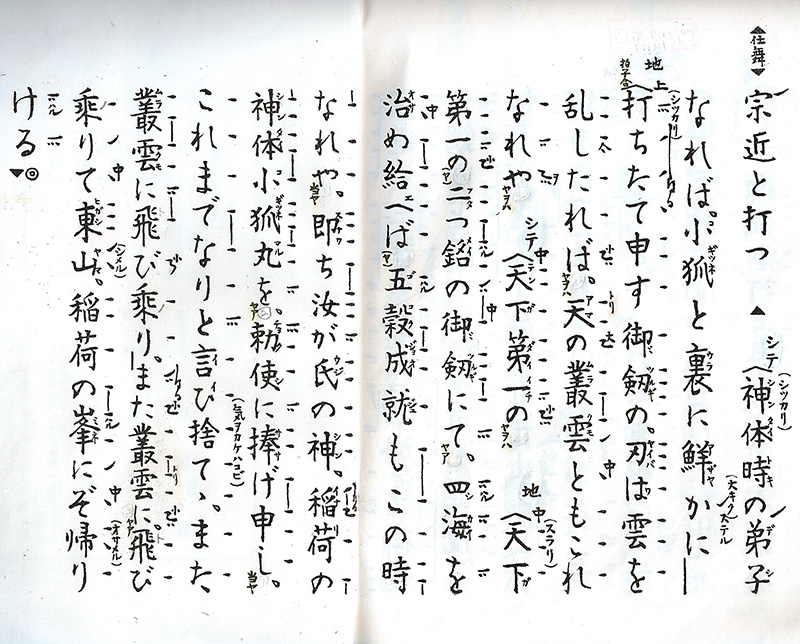

Dance – katatsuke

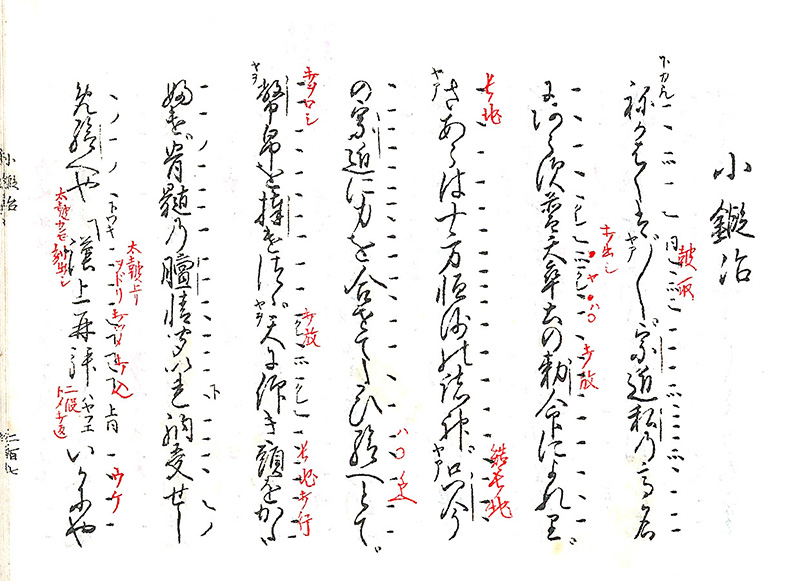

Increasing numbers of amateurs through 20th century led the headmasters of the shite’s schools to publish the choreography of the climactic part, shimai, in Noh plays. Movement patterns called kata, mostly indicated by their particular names, are written down side-by-side with the sung text (Fig.3).

Fig.3 Kongō ryū shimai katatsuke Vol.3. Published by Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo, published year unknown.

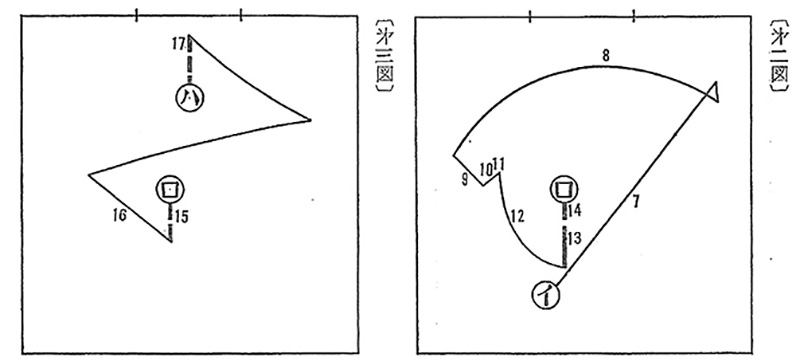

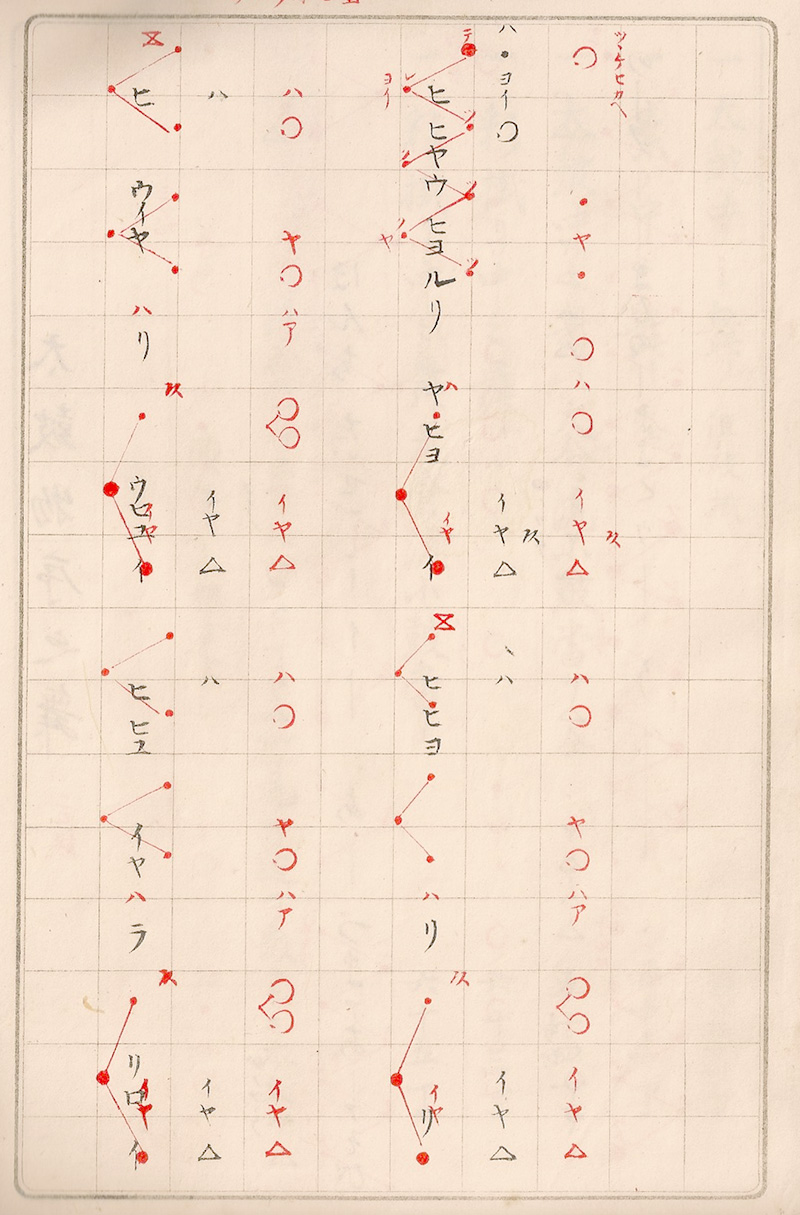

In early 20th century, some schools used diagrams to show students how to walk on stage in specific sections of a dance (Fig.4).

Fig.4 The diagrams of steps in Hashitomi’ Kuse’s shimai for dance students of Kanze school. (Quoted from: Kanze Motomasa, 1973, Shimai kōza Hajitomi kuse, Kanze 40(7): 19-21.)

Percussion – testuke

Compared to chant and dance, percussion performance, kotsuzumi, ōtsuzumi and taiko have not been practiced by many amateurs. Notation was not easy for beginners to understand. The original form of percussion notation consisted of names of patterns listed in the order they were to be performed (Fig. 5 & 6).

Fig. 5 Kotsuzumi’s notation for Jonomai. Patterns names of Kō school written down in the order they are performed. Manuscript. Author unknown.

Fig. 6 Kotsuzumi’s notation of Kokaji. Patterns names of Kō school written along the chanting text. (Quoted from: Kō Gorō, 1915, Kō ryū kotsuzumi tetsuke chi no maki ge. Published by Ejima Ihee, Tokyo.

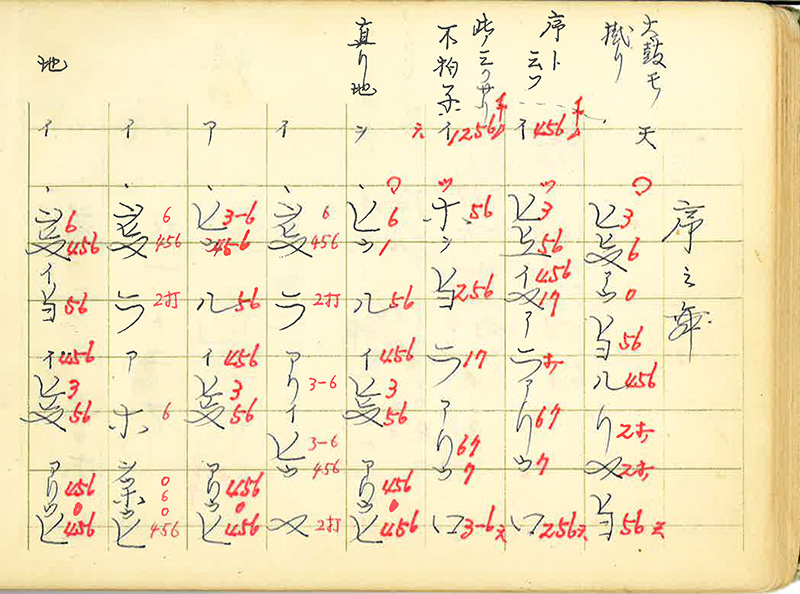

Following the increase of amateur players in the 20th century, some schools of drumming have published notation books with a clearer style that places all strokes and kakegoe vertically over eight beats frame, marked with lines (Fig.7). Chanted text or nohkan melody were then added, helping the percussion players synchronize their strokes and kakegoe to singing or nohkan melody.

Fig. 7 Percussion notation of Jonomai with strokes and kakegoe. Kotsuzumi’ are in red, ōtsuzumi in black, and taiko in red, layered on nohkan notation, from right to left. (Quoted from: Morita Misao, 1914, yōkyoku maibayashi taisei. Published by Yoshida yōkyoku shoten, Osaka).

Nohkan

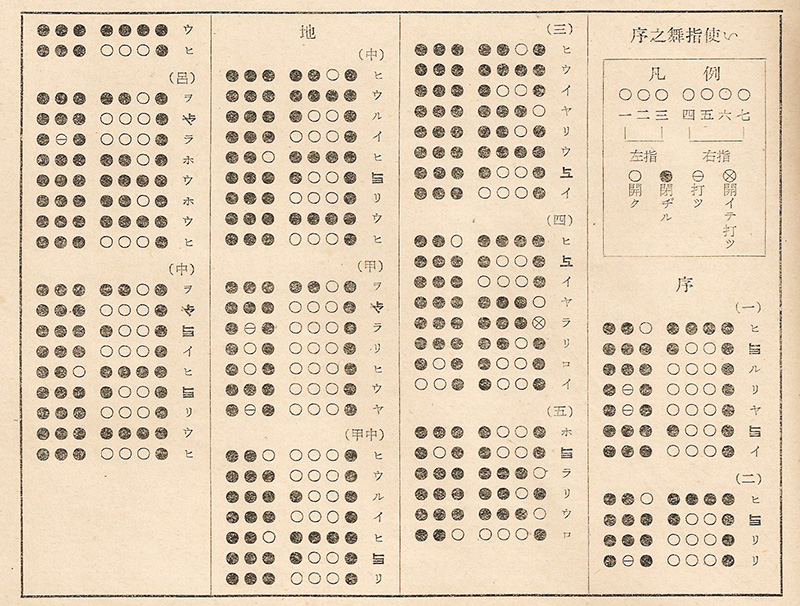

Nohkan uses oral notation called shōga, widely used for learning Japanese wind instruments. In Nohkan, shōga consists of fixed sets of Japanese syllables such as o-hya-ra or hi-u-i-ya, which remind players of particular basic melodies produced by fixed combinations of fingering patterns (Fig. 8 & 9). Having basic shōga melodies in mind, individual nohkan players create unique embellishments with fingerings added to the basic patterns.

Fig. 8 Shōga notation with appended fingerings shown with numbers in red. Manuscript by Akai Fujio, the nōkan players in 1980.

Fig. 9 The diagram of fingering patterns shown along the shōga notation. (Quoted from: Morita ryū shokubunkai, 1951, Morita ryū fue jonomai. Tokyo: Hinoki-shoten).

Full Score

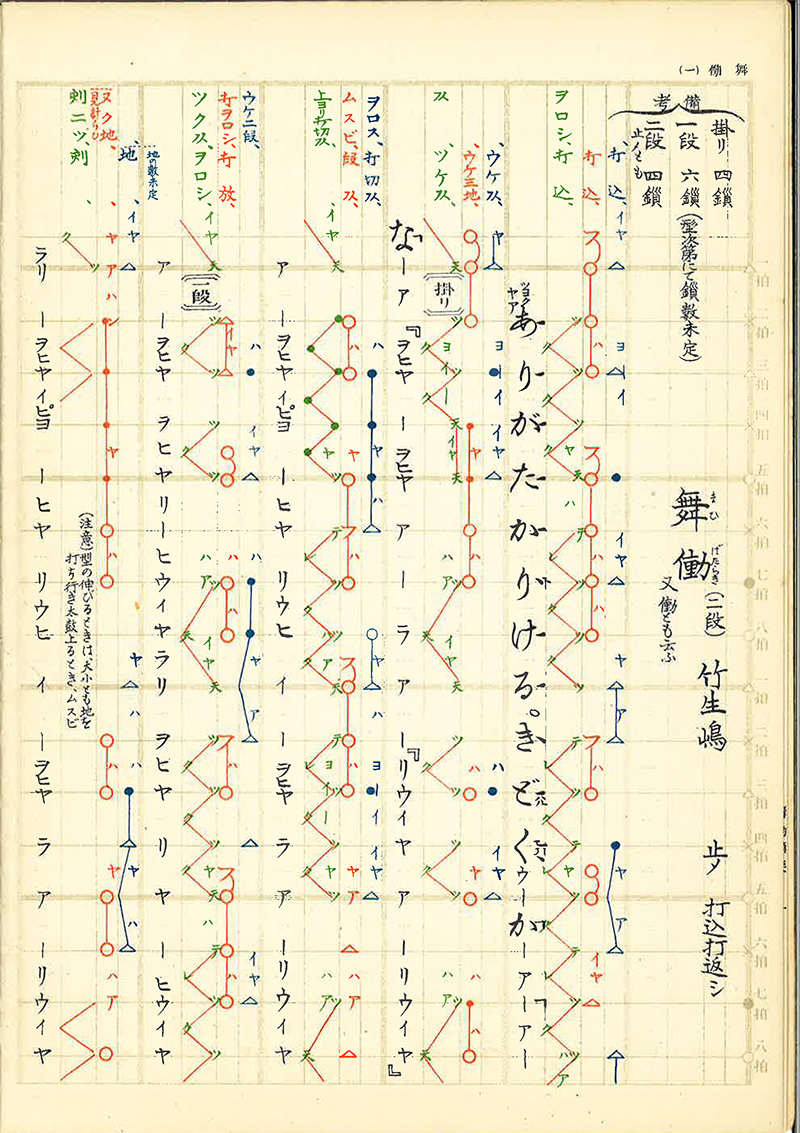

Having five schools for the shite’s chant and two to five schools for each instrument, the number of combinations of parts from all different schools are close to infinite. This is why full scores of Noh plays have rarely been created or published. In the history of transmission, however, some publications chose a single school for each part and notated chant and percussion patterns side-by-side, often using different colors (Fig.10). It may not have been useful for students of individual parts but it is invaluable for those who are eager to analyze Noh music. The notation used on this website is meant to serve a similar purpose.

Fig. 10 Score-type notation of Maibataraki made by an amateur musician, Tazaki Enjirō. Ōtsuzumi in blue, kotsuzumi in red, taiko in green and red, and the chanting text and nohkan’s shōga in black from right to left in a column. (Quoted from: Tazaki Enjirō, 1927. Shibyoshi tetsuke taisei Maibataraki. Tokyo: Hinoki-taikadō shoten).